Written by Kyle Walker taken from 2012 John Whitmer Journal

At the October 1845 conference of the church held in the Nauvoo Temple, which had only days before been opened for congregational worship, Lucy Mack Smith requested to speak to the thousands of Saints who had gathered. Church authorities who were present on the occasion enthusiastically granted her request. As far as I can document, never before had a female been afforded the honor of speaking during a General Conference meeting, and it evidenced the special place she held in the hearts of all the Saints. At one point during her remarks she made reference to her being a mother to the church, and told the congregation she considered them her children. “If you consider me a mother in Israel,” she asked of those present, “I want you to say so.” Brigham Young then arose from his seat near the stand, and invited members of the audience who considered Mother Smith a Mother in Israel to signify it by saying yea. All those present affirmed her request, with “loud shouts of Yes.”

After she had finished speaking, Brigham Young spoke to the congregation where he declared, “I pledge myself in behalf of the authorities of the Church that while we have any thing they [Lucy and her family] shall share with us.” Young then counseled the congregation in regards to Lucy, “I want the people [sic] to take anything they have to her [and] let her do with it what she pleases.”[i] While Lucy’s experience at the conference underscores the veneration the Saints held towards the Smiths, Young’s commitment to the Smiths would be tested in the coming months, as the Smiths chose to remain behind and the majority of Lucy’s children would not support his leadership.

Much has been written to document the differences that emerged during this crucial time period between Emma Smith and Brigham Young, as well as the variances between Smith cousins in the latter part of the nineteenth-century after the Reorganized Church was established.[ii] While these relationships constitute an important aspect of what occurred during this era, these interactions do not tell the whole story. Considering the vast contributions of the Smith family, and the appreciation held by Saints who eventually went west, one would expect there to be much efforts expended in ensuring that the Smiths were cared for following the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. This article will examine what efforts were made by the Twelve and those who eventually went west in supporting the Smiths.

By August 1844, only five of the original eleven members of the Smith family were still living. This included Mother Smith and her three daughters: Sophronia, Katharine and Lucy, and the only surviving male member of the family, William. William would be delayed nearly a year after learning of the murder of his brothers, as he cared for his severely ill wife in the East, and continued to oversee the church in that area. This left only the female portion of the family in Illinois, where each of the three Smith sisters were married and rearing their families.

Eldest daughter Sophronia was married to her second husband William McCleary, and was the most financially stable of the surviving Smiths. The McClearys had lived in Ramus prior to the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum, but the family moved to Nauvoo shortly thereafter. Daughter Lucy, the youngest of the family, was married to Arthur Millikin. According to at least one account, Arthur struggled to maintain a consistent livelihood during this time period. At a later date he was listed as a saddle and harness maker, and may have earned some money by laboring at that trade at the time the main body of Saints was making preparations to go west. Financial challenges notwithstanding, the Millikins led out in looking after Mother Smith in her declining years.[iii]

Middle daughter Katharine, who was married to a blacksmith named Jenkins Salisbury, lived forty miles away in Plymouth, Illinois since migrating from Missouri. By the summer of 1844, the Salisbury’s family connection to the Prophet was well known to neighbors, and they lived outside the protection that Nauvoo afforded during this time of hostility. In the months following the Carthage tragedy, neighbors tacked notes to their door that threatened the family that if they did not leave the community their home would be burned to the ground. The Salisburys left Plymouth in August 1844, and after a series of calamities, eventually arrived at Nauvoo destitute of means.[iv]

As the surviving Smiths gradually gathered to Nauvoo for both safety and support, Church authorities were attentive to the family’s needs. They were especially conscious of Mother Smith, due to her need for care as a widow and because she was in mourning. In less than four years, she had lost her spouse and four sons, including three sons during the summer of 1844. Lucy lived with her daughter-in-law, Emma Smith, for the remainder of that summer. As early as September 1844, two months after losing her sons, church leaders recognized Lucy’s difficult plight, and stepped in to assist in caring for the family. Church authorities rented the Jonathan Browning house at Nauvoo, where Mother Smith and her youngest daughter Lucy and her family lived for about a year. Authorities also hired a young lady, possibly Samuel’s daughter Mary Bailey Smith, to wait upon Lucy in ensuring her needs were met.[v]

Church leaders also provided emotional support for the grieving mother. When Apostle Wilford Woodruff prepared to leave for a mission to England in August of 1844, he made sure he visited Lucy prior to his departure. He found “the old Mother and Prophetess felt most heart broaken at the loss of her children,” and during their visit she requested a priesthood blessing from under his hands. Woodruff complied with her request, offering words of consolation. “Be Comforted in the midst of thy sorrow,” he proclaimed, “for thou shalt be had in honorable rememberance forever in the Congregations of the righteous.” Woodruff also addressed any distress she likely was experiencing regarding her economic status, when he indicated that “thou shalt be remembered in thy wants during the remainder of thy day[s].”[vi]

Brigham Young was also sensitive to the Smiths monetary condition. While speaking to the Saints some months after Woodruff’s exchange with Mother Smith, Young said that he wished the Bishops of the church would visit Lucy more frequently, but felt they had done “pretty well” in looking after her needs.[vii] Young personally would expend considerable effort in the ensuing months in ensuring the family was cared for. Leaders at Nauvoo also made sure they kept William informed as to his family’s condition. After receiving a letter from William in the early fall of 1844, Young recounted to William that he took his letter “and read it to your mother and sisters, and they rejoiced exceedingly to hear from you.”[viii] Other Saints in the city kept William informed on family matters, including Jonathan C. Wright, who reassured the traveling apostle, “give yourself no uneasiness about your mother—the Twelve say she shant want.”[ix]

In the meantime all the family anxiously awaited the return of their only son and brother William. They greatly missed his presence during this difficult and grief-stricken time, and hoped that upon his return he would assume a patriarchal role in the family. Mother Smith wrote to William in the fall of 1844, indicating,“We look to you as the sole remaining, male support of your Fathers house.”[x] Due to the prominent place he held within the family, William’s views strongly influenced surviving Smith family members after his return to Nauvoo in May 1845. Much of the untold story about the relationship dynamics between Smith family members and the Twelve during this time period revolves around William Smith.

William had experienced a turbulent history with his fellow quorum members throughout his tenure as an apostle. On at least six separate occasions, four prior to the martyrdom, his behavior was severe enough that his standing in the church had been called into question by his colleagues. With the exception of the final instance, when he was severed from the church, each time he had barely managed to retain his standing—typically through the intercession of his brothers Joseph and Hyrum while they were still living.[xi]

What upset those who were closest to William was his demeanor related to his calling and position in the church. From his early twenties it became evident that Smith manifested a sense of entitlement as it related to both his ecclesiastical positions and as a member of the founding family of Mormonism, and it often exasperated those with whom he served. This was especially so in his calling as a member of the Twelve. Within months of his call to the quorum in 1835, Orson Hyde complained about William receiving more assistance from the Bishop’s storehouse than any of the rest of the Twelve. Hyde complained to Joseph Smith, “not long since I asertained [sic] that Elder Wm Smith could go to the Store[house] and get whatever he pleased . . . until his account has amounted to seven Hundred Dollars.” “While we were abroad this last season,” continued Hyde, “we strain[e]d every nerve to obtain a little something for our family’s and regularly divided the monies equally . . . not knowing that William had such a fountain at home from whence he drew his support.” He petitioned the Prophet to rectify the disparity. Joseph Smith was obligated to intervene to resolve Hyde’s concerns, and afterwards arranged the storehouse to ensure that credit was extended equitably to members of the Quorum of the Twelve.[xii]

If that had been the only complaint against William perhaps it would go unnoticed, but the experience did not change William’s disposition, as he continued to regard it as his prerogative to be taken care of at a greater level than that of his colleagues in his ministerial duties. His behavior, as highlighted by Hyde in 1835, would be repeated time and again throughout his life. While other members of the Twelve would receive financial assistance due to their full-time labors in the ministry, none received the level of support that William had, nor interpreted the scripture “the labourer is worthy of his hire” (Luke 10:7) to the extent he did.

Smith’s struggles with entitlement appear to have reached a crescendo after he returned from his eastern mission in 1845. He felt entitled to church properties, eventually going to such lengths as expecting one-twelfth of all the tithing of the Saints. Authorities were initially sympathetic to Smith’s desires. Shortly after he had returned, Brigham Young encouraged Nauvoo’s citizens to support William. Said Young in a meeting of the Saints,“remember bro Wm. Smith – he has had a sick family. Father Smith was alive with Sons, and all are gone but brother William, be kind to him [and] don’t be afraid[?] of your substance and the Savior will bless you.”[xiii] Young indicated that shortly after William arrived in Nauvoo, “we furnished him a span of horses, and a carriage and a house, and Brother [Heber C.] Kimball became responsible for [paying] the rent of it.”[xiv] William and his mother, along with Katharine, daughter Lucy and their families, lived together in the commodious William Marks’ home on Water Street. William was also allowed to charge for his patriarchal blessings in Nauvoo, and by that means he obtained his livelihood.[xv] The church was completely supporting William, and providing housing for the rest of the family, with the exception of Sophronia.

William did little to assist his mother and sisters after he returned to Nauvoo. Though Lucy hoped he would assume the role as the family’s “sole remaining support,” rarely, if ever, had he enacted such a role in the family, and it would be no different this time around. As Lavina Fielding Anderson summarized, while “William was in a sorry financial plight himself, it is also true that there is no record of his contributing in any way to Lucy’s support. Rather, his public expressions of pity and concern for his ‘poor old mother’ can be read, without any great stretch of the imagination, as designed to raise funds and bolster his claims to authority within the church. . . . William’s future public statements also tended to be along these same lines: making use of Lucy’s age and poverty to rouse pity and open pocketbooks.”[xvi]

William instead expected the Twelve to care for himself and his family. Later that summer, when William wrote to Brigham Young requesting an additional $75.00, Young informed him that they did not have the money to pay him and that he had “already received more assistance from the church funds than all the rest of the Twelve put together.”[xvii] It was a familiar refrain, and when his expectations were unmet William became increasingly dissatisfied.

A final episode occurred in August 1845, when Brigham Young was constructing a carriage for his family. Young had apparently promised Mother Smith a ride in the carriage when it was finished. Lucy had often enjoyed going on carriage rides with her son Joseph before his death, and it was kind gesture by Young. However, once William learned of the carriage, he started a rumor that his brother Joseph had been constructing the carriage for his mother prior to his death. Thus, he encouraged his mother to not simply to ask Young for a ride, but to give her the carriage, a horse, and a harness. Young was obviously surprised at this turn of events, but was quick to ensure that no hard feelings should exist between them. He wrote to Lucy immediately, informing her that when the carriage was complete she should have anything her heart desired. “All that I have is at your command to make you happy [in] the little time you have to live with us,” Young wrote reassuringly. He also expressed his desire to call on her as soon as it was convenient, and concluded, “may the Lord Bles[s] you and comfort your h[e]art—I am your son and fr[i]end as ever.”[xviii] In the end, Young decided to let Mother Smith have the carriage so that she could have the comfort of riding around the city until her death, as well as to avoid any rancor. William Clayton summarized in his journal, “out of respect for Mother Smith the brethren would rather indulge the whole family than to have hurt feelings.”[xix]

While William sparred with leaders throughout the summer of 1845, church leaders manifest rather remarkable patience as he jockeyed for a more prominent role in the church’s hierarchy. William frequently complained that not enough was being done to honor his family.[xx] Sensing William’s frustrations, his brethren of the Twelve hit upon the idea of hosting a dinner for the entire Smith family and all their relations. The purpose of the dinner was to honor the family for the significant role they had played in the Restoration, and recognize the losses and persecution they had experienced as a result. They were especially conscious of William, encouraging him to invite any and all of his friends to the celebration as well. Leaders ensured that carriages were employed to transport all members of the family to and from the Mansion House, where the dinner was held. Bishops Newel K. Whitney and George Miller hosted the celebration on behalf of the Church, while Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball and other members of the Twelve waited on the Smith family. The dinner celebration lasted from 2 p.m. until dark, and included entertainment by a band. As the festivities came to a close, Mother Smith affectionately addressed her kindred and the audience. William also offered a benediction of thanks to all those involved, and then proposed a toast: “In the name and on behalf of all my relatives here assembled, the whole Smith family, I present my thanks to the President and Bishops for the kind manifestation of their good feelings towards the remnants of that family.”[xxi]

The expression of goodwill by church leaders only temporarily assuaged William’s feelings however, and within a short time he was again at odds with his colleagues. He clashed with his brethren of the Twelve on a variety of issues, including the scope of his authority as the presiding patriarch, control of the Nauvoo police, and audaciously preached a public sermon on plural marriage. He was severed from the church that fall, after he fled Nauvoo and published a lengthy pamphlet that denounced the Twelve.[xxii] Young initially held out hope that William would return, when he recounted that Smith had “run away in a time of trouble; but I suppose will come back when it is peace.”[xxiii] In time, he and other leaders at Nauvoo realized William was opposed to the Twelve to the point of creating a rival organization. This created somewhat of a conundrum for Young and other leaders, who certainly longed to see all of the Smiths united in their support of the Twelve.

The first time Smith returned to Nauvoo after his excommunication was in March 1846, just after Brigham Young and his followers left for the West. The timing of his return was not coincidental. Smith not only had aspirations of gathering up those who remained behind to support his leadership, including his own family, but he also vied for property which had been left behind by the church. Church trustees who remained at Nauvoo quickly ascertained Smith’s motives, and he was given a chilly reception by those who remained behind.[xxiv]

Shortly after he returned, William learned of a promise church leaders had earlier made to his mother to care for her during her final years. One year earlier, on July 24, 1845, trustees at Nauvoo paid $100 for a lot that they gifted to Lucy.[xxv] About a week later, on August 2, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball purchased several blocks of property in the heart of Nauvoo from Emma Smith for $550. This not only assisted Emma in providing for her family, but would ensure Lucy and her daughters were looked after as well. William Clayton recorded that the authorities “then went to Mother Smiths and took her into the Carriage to show her the Blocks and give her her choice which of the two she would have to be deeded to herself and her daughters.” After Mother Smith chose her lot, she requested they build her a home similar to Heber C. Kimball’s, one of the finest structures in all of Nauvoo.[xxvi] However, with the hurried migration, leaders knew they would be unable to construct such a home, and instead, discussed with Mother Smith alternative options that would ensure that her needs were met for the remainder of her life. According to Orson Hyde, the presiding authority left behind at Nauvoo in the Spring of 1846, “we offered to pay Mother Smith two hundred Dollars yearly, and furnish her a house to live in rent free, and pay the amount monthly or quarterly.” The church appointed trustees, Almon Babbitt, Joseph Heywood, and John Fullmer, were assigned to complete the details of the transaction.

Lucy felt satisfied with the arrangement which would allow her the comforts of a home, and the proposed monthly allowance would provide for her basic necessities during her final years. To the trustees’ surprise however, once William arrived in Nauvoo he stepped in to act as an intermediary between trustees and his mother, and advised his mother to refuse the offer. William encouraged his mother to make as “large a grab” as possible, which meant obtaining legal title to an existing home in Nauvoo as opposed to the yearly salary and rent-free home. He was afraid that once the Saints left for the West, she would not see the promised monies. Orson Hyde felt that William’s motives were more self-serving, in that he desired to obtain the property for himself after his mother’s death, which subsequent history reveals was precisely his motive.[xxvii]

The trustees, led by Almon Babbitt, were uncomfortable negotiating with William, and were hesitant to make the transfer. After all, the trustees, including Orson Hyde, were well aware of Smith’s track record in terms of requesting church funds. To add to their discomfort, Smith was also now openly supporting James J. Strong’s movement. [xxviii]

Babbitt and Heywood met with Mother Smith on March 10, 1846, and according to William, informed her that if they did not acknowledge the Twelve the Smiths would not receive an inheritance. However, it soon became apparent that their concern was not so much with Mother Smith as it was with William. After a few weeks, trustees wrote to Mother Smith informing her that they would not transfer the home while she allowed “William to stay about her house.” Trustees were concerned about Smith’s motives and his influence on remaining Saints in Nauvoo now that he was supporting Strang, but the request was insensitive and unrealistic. The letter didn’t reflect well on the trustees, as a widow would certainly desire her only remaining son to be at her house as often as possible. This was not the first time that Almon Babbitt had offended members of the Smith family, as he had been particularly injudicious in his consultations with Emma Smith during this same time period.[xxix] It was an error in judgment on Babbitt’s part, that didn’t reflect well on the church. At the same time, it’s understandable why trustees were hesitant to negotiate with William.

Mother Smith responded indignantly towards the trustees and took exception to their request regarding William; “You would have me forsake my children in order that you may give me a living, but let it not be said that in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, a mother has to forfe[i]t . . . the cords of affection that bind her to her children, or she shall not have a subsistence.” She reminded them of Brigham Young’s promise of a home before he had left for the West, revealing her sentiment that “I think if he were here he would not do as you have done.”[xxx] Lucy’s statement revealed her positive feelings towards Young and other leaders who had left for the West. She blamed the trustees for the insensitivity, while William blamed Young.

The trustees wrote to Brigham Young seeking counsel on how to proceed in supporting Mother Smith now that William had interfered with their original agreement. Hyde recounted to Young, “We offered to pay Mother Smith two hundred Dollars yearly, and furnish her a house to live in rent free, and pay the amount monthly or quarterly, but “Bill” [William] puts the old lady [Lucy] up to refuse that offer. He wants a good property deeded to her, that at her death he may have it. We are not disposed to do it, unless you counsel us to do so. We have told the old lady [Lucy] that we are willing to support her handsomely.”[xxxi]

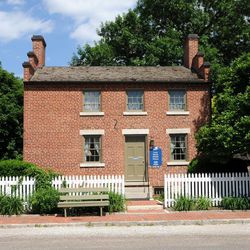

While the particulars of Young’s response have not survived, he appears to have directed them to either give her title to a home at Nauvoo or the yearly salary, leaving the decision to be worked out between the trustees and Mother Smith. Immediately after receiving Young’s directive, the trustees recognized their error in the way they had handled the situation and began discussing these options with Mother Smith and her son-in-law Arthur Millikin. Tellingly, William was absent from the discussion. Millikin proposed that he would be willing to care for Mother Smith for the remainder of her life if there was some “inducement” at Nauvoo that could be “secured to him,” evidence that he was struggling to maintain a livelihood as a harness maker at Nauvoo after the departure of Young and his followers. The two parties agreed that if trustees purchased the Joseph B. Noble home for Mother Smith, she would, in time, transfer the title to the Millikins. Millikin agreed that if he would ultimately receive title to the home, he and his wife would ensure that Mother Smith was provided for until her death. All parties felt satisfied with the arrangement, and trustees purchased the home from Noble, and then transferred the property to Mother Smith on April 11, 1846. George A. Smith recorded two days later, “The trustees gave mother Smith a deed of conveyance of a house and lot, in the city of Nauvoo, built and occupied by Joseph B. Noble, valued at twelve hundred dollars, which she took possession of.”[xxxii]

However, in order to combat William Smith’s persisting complaints against the Twelve, the trustees at Nauvoo created a document certifying that church leaders had been equitable towards the Smith family. Trustees printed the contents of the document on a broadside entitled To the public, and its introduction read in part: “The following document . . . will show how much honesty, sincerity, or good faith, there is in Wm. Smith’s pretended claims to any portion of the Church property. In the first place, he had no claim: But, to avoid any difficulty or contention, the Trustees agreed to give to his mother the property.” The document was signed by William Smith and his sister Lucy and her husband. Trustees felt that this approach was necessary to combat William’s claims of neglect against the church that had irritated church leaders for many months. The document read as follows:

This is to certify , that we, the members of the Smith family, in consideration of Mother Smith have received from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a deed of conveyance of a house and lot in the city of Nauvoo, Hancock county; built and occupied by Joseph B. Noble, valued, in ordinary times, at the sum of twelve hundred dollars. We hereby in consideration of the above named and mentioned donation, and deed of conveyance, declare ourselves perfectly satisfied with the dealings of said church with Mother Smith; and freely acknowledge that the said church is hereby released from all moral and legal obligation to us or either of us. In testimony whereof, we have hereunto set our hands, this thirteenth day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty six, at Nauvoo, Hancock county, Illinois. Wm. Smith, Arthur Millikin, Lucy Millikin.[xxxiii]

Though authorities righted the wrong, William would continue to bring up the slight that had occurred before the transaction was consummated for many years afterwards, in each organization in which he affiliated. He persisted in his accusations against the brethren that they had robbed the Smith family of their rights to monies, failing to mention anywhere that church leaders had, in the end, given his family title to the Noble home.[xxxiv] When LDS leaders learned that Smith continued to charge them with neglect, they felt indignant towards the former apostle. To counter William’s persisting accusations, Orson Hyde wrote an article in the Frontier Guardian explaining the circumstances which defended their efforts to support the Smith family. Hyde wrote specifically about transferring the Noble home to Mother Smith, and recounted for his readers, that the Smiths had released “the Church from any further obligation for Mother Smith’s support” at that time. “These are the facts of the case,” continued Hyde, “and if William does not remember the whole circumstances, we will refresh his memory.” [xxxv]

Accusations reached a climax when Young and Smith accused each other of being involved in the murder of Irvine Hodge, which had occurred in the summer of 1845. Though evidence suggests that neither man played a role in the Hodge murder, it reveals how rumor and innuendo influenced both men’s views of one another, and tainted the relationship between church leaders in the West and the Smith family.[xxxvi] At a later date, William went so far as to accuse Young of the murder of his brother Samuel. Unfortunately, William had muddled his timeline, as Young was in the east with other members of the Twelve, including William himself, at the time Samuel died in Nauvoo. Such rumors had their impact however, as many Smith family members for generations were led to believe in William’s unfounded accusations about these events in the wake of his brother’s deaths. The Smiths and many of their descendants came to believe that Young had neglected their family, caused Samuel’s death by administering poison, and robbed the Smiths of their rightful inheritance.[xxxvii] On the other hand, William was branded a rogue among Latter Day Saints in the West. This set the tone for the impasse that existed between Saints in the West and the Smiths ever afterwards.

When William Smith linked his aspirations with Strang in the years 1846-47, the Saints on the westward trek took notice. Particularly concerning to Brigham Young and the Twelve was William’s influence on the remaining Smith family. Young and his followers were surprised to learn of Strang’s success in gathering up some of those Saints who remained behind, and expended efforts in countering his influence. Both Young and Strang longed to have the support of the Smiths. Due to William’s tendency to make unsubstantiated statements, the level of support for Strang from William’s sisters and mother is largely a matter of conjecture. Still, Young heard rumors that the whole Smith family was supporting Strang, as William publicly declared via Strang’s newspaper.[xxxviii] In January 1847, Young recorded a dream regarding Mother Smith: “I dreamed of seeing Joseph the prophet last night and conversing with him, that Mother Smith was present and very deeply engaged reading a pamphlet, when Joseph with a great deal of dignity turned his head towards his mother partly looking over his shoulder, said, ‘Have you got the word of God there?’ Mother Smith replied, ‘There is truth here.’ Joseph replied, ‘That may be, but I think you will be sick of that pretty soon.”

Later that same month Young’s thoughts were again on the Smith family, as he wrote of Mother Smith and William living together at Knoxville. Speaking of Lucy, Young recorded, “at the last report she was a Strangite, but we think she will not be [for] long.” He then wrote amiably, “it would rejoice our hearts if Mother Smith [were] was with us so that we could minister to her necessities.”[xxxix]

Young feared losing the Smiths, as their support would evidence unity within the church. He also knew that Lucy’s support was instrumental in obtaining the family’s support. On April 4, 1847, as Young prepared to depart Winter Quarters to complete their epic migration to the Rocky Mountains, he paused to write one more letter to Mother Smith. “Beloved Mother in Israel,” he began, “our thoughts, our feelings, our desires and our prayers to our Heavenly Father, in the name of Jesus, are often drawn out in your behalf.” “We felt that we could not take our leave without addressing a line to Mother Smith, to let her know that her children in the Gospel have not forgotten her. . . . If our dear Mother Smith should at any time wish to come where the Saints are located, and she will make it manifest to us, there is no sacrifice we will count too great to bring her forward, and we ever have been, now are and shall continue to be, ready to divide with her the last loaf.”[xl] Though Lucy remained in the Midwest, she and her daughters remained positive towards those who later visited them from the Salt Lake valley.

After Brigham Young and his followers had settled themselves in the West, they continued to be mindful of the Smith family. The three Smith sisters remained in the vicinity of Hancock County in the decades after the martyrdom. Of the three, Katharine was the most impoverished, compounded by her husband’s untimely death in 1853. Her sister Sophronia, who was economically better off, stepped up to lend her support by providing a quality education for one of Katharine’s sons, who she helped to raise. Still, Katharine’s plight was difficult. Financially destitute, Katharine finally wrote to Brigham Young requesting funds to help her build a home in Hancock County. With all that had transpired between leaders in the West and Smiths by this point in time, it is intriguing that she would turn to Young for support. One wonders also how Young felt about the request, as it was readily apparent that the remaining Smith sisters had not supported his leadership.

On April 29, 1871, she wrote to Brigham Young requesting two hundred dollars to help her build a small home in northeast Fountain Green. Brigham Young wrote back, sending the desired amount of money and expressing his concern for the Prophet’s family who remained in Illinois. Young wrote warmly, “I send you Two hundred (200) dollars at your request, and I sincerely trust it will prove the blessing you anticipate.”[xli] After receiving the money from a traveling missionary, Katharine expressed her gratitude, indicating that she was certain the money would prove to be “the Blessing I desired of it and I feel Shure the Lord will bless the doner of the gift.”[xlii]

Apparently Katharine underestimated the costs associated in constructing her home, and she wrote several more times in the ensuing months requesting additional funds. In several different payments, Young eventually sent an additional $600 so that Katharine could finish her home and consolidate her land.[xliii] Katharine continued to correspond with Brigham Young and his first counselor, and her first cousin, George A. Smith. For a time, at least, President Young’s generosity seemed to heal former misunderstandings. Katharine wrote to Young at one point, “My gratitude to you is unbounded and i Shall ever pray for blessing[s] to rest uppon your venerable head . . . . I will send you my likeness [photograph] . . . and wish you would send me yours in return that i may look uppon [it] with thankfullness for the great help you have rendered to me in the hour of my greates[t] need.”[xliv]

George A. Smith visited Katharine in 1872, and wrote Young describing her living situation and of her gratitude for the financial gift. “[K]atherine is living on the place, that you furnished her means to purchase,” wrote Smith after visiting her residence, “and is . . . the happiest Woman I have seen on the journey[.] her place is a piece of Timber land, which your last bounty enables her to increase to twenty acres. And as in all her live [life] she has never been able to enjoy a home of her own for a single hour, her gratitude to you seems unbounded.”[xlv]

The gift apparently did not fit RLDS rhetoric about Young’s caricature as being hostile and neglectful towards the Smith family, and Katharine’s descendants in turn surmised that the monies were sent to pay for her to come to Salt Lake City to gather with the Saints.[xlvi] This was incorrect, as Katharine specifically had requested the money to build a home in Fountain Green, Illinois, and Young had sent the money for that express purpose. Katharine responded to each financial gift by expressing her appreciation to LDS leaders, including her desire that she “would like very much to See you all once more before we depart this life. May the blessings of heaven rest upon you and all the church.”[xlvii]

Following Brigham Young’s death in 1877, Katharine kept up a correspondence with LDS leaders in the West, and these individuals continued to provide financial assistance for Katharine in her poverty. By the late 1870s Katharine still owed a significant sum of money on her land, which she had expanded to forty acres in the intervening years. When a new owner assumed her mortgage he threatened to evict her from the property if she could not make regular payments. Katharine wrote to several leaders, including President John Taylor begging for assistance to retain her property.[xlviii] Joseph F. Smith, Katharine’s nephew and LDS apostle, was less inclined to use church funds to support Katharine than had been Young, for he knew that she and her sons were affiliating with the RLDS Church. He thought they should first go to their own leaders for support. Notwithstanding these reservations, through Joseph F. Smith’s intercession, he persuaded John Taylor to send another $300 to Katharine to ensure that creditors would not foreclose on her home. Taylor’s secretary, L. John Nuttall, recorded, “I met with the council of Apostles at 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. $300.00 was appropriated in behalf of Katherine Salisbury, sister of the Prophet Joseph Smith, to save her home.” The monies enabled her to remain in her home and retain her property, where she lived with her youngest son Frederick for the remainder of her life, nearly thirty years after Young’s initial generous gift.[xlix]

Brigham Young, along with the assistance of other church leaders, had generously provided for the surviving Smiths after the summer of 1844. George A. Smith later summarized the feelings of the Saints in the west towards William in particular when he lamented, “The Saints could have carried William upon their shoulders; they could have carried him in their arms, and have done anything for him, if he would have laid aside his follies and wickedness, and would have done right.”[l] Truly they had supported William both financially and emotionally after his return to Nauvoo, until he had exhausted nearly every resource extended to him, and exploited their generosity. Though his personal struggle was complex in the months after his return to Nauvoo, he ultimately fled Nauvoo in the fall of 1845 and left this very comfortable situation. He eventually regretted his decision to leave, wishing to be restored to his previous callings in the LDS Church on multiple occasions. Leaders in the West felt that his confession was unsatisfactory and were hesitant to restore him to his place in the Twelve or as Patriarch.[li]

As for Mother Smith, she had been offered a home free of rent and a yearly salary of $200, only to instead request a home of her own due to William’s solicitations. At the encouragement of Brigham Young, trustees at Nauvoo eventually deeded the Joseph B. Noble home to her outright. Lucy was content in finally having a home of her own, and lived at the residence throughout the summer and early fall of 1846, before fleeing the city to avoid the Battle of Nauvoo in the fall of that year. When she returned in the Spring of 1847, she went ahead and deeded both her home and an additional lot that had been deeded to her by trustees to the Millikins, according to the initial arrangement.[lii] Her daughter Lucy and her husband continued to care for the aged matriarch during her final years, as they lived together in the Noble home until 1849, before moving to Webster (formerly called Ramus).[liii]

While Emma Smith Bidamon is rightfully credited for caring for Mother Smith for several of her final years, the Millikins had served as her caregivers during an eight year period from 1844-52. In 1852, the Millikins sold the Noble home at Nauvoo, and decided to migrate eastward to McDonough County, Illinois. In selling the property, the Millikins also profited from the Twelve’s generosity.[liv] Mother Smith, desiring to be closer to her deceased loved ones, moved in with Emma and Lewis Bidamon that same year. The couple, along with the assistance of granddaughter Mary Bailey Smith, affectionately cared for Lucy during the final four years of her life.[lv]

In the end, leaders of the LDS movement who settled in the West had provided homes and financial support for four of the five remaining Smith family members—all of those who were in need. This supportiveness did not end once the Smiths began affiliating with the RLDS Church in the 1870s, as evidenced by Brigham Young’s willingness to send Katharine substantial sums of money to help her construct a home and purchase forty acres of land in Fountain Green, Illinois. Leaders in the West continued to send funds to help Katharine maintain her home and property after Young’s death in 1877.

While there were certainly differences that persisted between church authorities in the West and the remainder of the Smith family after the summer of 1844, Brigham Young and other church leaders remained generous and supportive to the Smiths. Young said at one point, “I do not know but that I would have taken off my shirt and given it to any of the Smith family and run the risk of getting another.”[lvi] It was not just rhetoric, as Young and other church leaders backed up this sentiment by making great exertions towards supporting all the Smith family. In a letter he penned to Katharine when he first sent money for her to purchase a home, Young wrote, we “convey to you our best regards. The memory of our beloved Prophet is deeply cherished in the hearts of the Saints, and for his sake, his relations and members of his family, notwithstanding differences of opinion[,] are kindly regarded and would be welcomed among us and received with open arms . . . . May peace be with you and the blessings of Heaven attend you all the remnant [remainder] of your days upon the earth, and a happy hereafter be your lot in eternity. Your Bro. in the Gospel –Brigham Young.”[lvii]