Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith

In a remarkably concrete version of preparing for the brighter day, Joseph Smith had told the early Saints to build cities. The way to bring in the millennial reign was to gather people into cities of Zion. He even provided a plat with block layouts and instructions for farmers to live in towns and commute to their outlying farms each day. He instructed them in how to form an egalitarian economic system that would eliminate poverty and assure industry. In short, he gave them a blueprint for a millennial city, and then told them to build first one and then another and so fill up the world in the latter days.

Joseph Smith’s grand, even grandiose thinking, was more than a projection for his small band of followers. His was a plan for the whole country which he would fill up with cities of Zion in the latter days. His one projection for the tiny group of Mormons living in cabins in Jackson County, Missouri, was actually a blueprint for America’s future: a nation of cities, established on principles of equality and dedicated to unity and righteousness — godly cities in the best sense where everyone could thrive and worship. He put temples at the center of his cities to exemplify the pursuit of godly intelligence, his great ideal.

The Mormons in Utah thought of themselves as fulfilling Joseph Smith’s millennial vision. Their aim was to build the godly cities Joseph had seen as America’s future and the prelude to the brighter day. I doubt that he knew in 1831 the Saints would one day head to the Great Basin, but he was in effect teaching them how to settle an open country — how to organize their communities when they arrived. In fact, his plans for millennial society could be fulfilled only in open country with no preceding towns in place. Whether he knew it or not, he was from the beginning preparing the Saints to be pioneers.

Pioneers entering the Salt Lake Valley in 1847

Pioneers entering the Salt Lake Valley in 1847

When the challenges of the Great Basin were thrust upon them, the Mormons were ready. From the time of the Church’s organization, they had been trained to have hope and to build societies. In Deseret, they held on to their meager farms in a forbidding environment because their goals went beyond their own comfort and prosperity. They were building a millennial society as instructed by their prophet, according to the pattern he had foreseen for all of America. In settling the West, they were unfurling Zion’s banner for all of humankind to look upon.

The question arises, of course, who was to enjoy the brighter-day? Was Zion for Mormons only? The prophecies of the Second Coming were enmeshed in predictions of calamities — wars, earthquakes, pestilence — that would bring ruin on the wicked. Dire warnings had been part of apocalyptic religion from the time of Ezekiel and Daniel in the Hebrew Bible. Did this imply Zion was a refuge for the Saints and none other? The Zion ideal promised peace and unity — people were to be of one heart and mind. Did that mean all but right-thinking Mormons were to be excluded?

If so, Zion in the West was doomed to failure. The Great Basin was a slate on which the Mormons could inscribe their own particular way of organizing society, but it was also part of the wide open spaces. Wide open meant space for the Native Americans who first possessed the land, and then for anyone else who rode in and settled. And many did come, not just the Mormons. There were railroad workers and miners who were largely non-Mormon, and people of many religions and ethnicity: Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Catholics, Jews, Italians, Asians, Greeks. Not many years after the Mormons came, the region was profoundly multicultural, as were virtually all western territories. People of all kinds went west looking for a brighter day. There was no way to shut the gates on the diverse, polyglot, multi-ethnic influx and to preserve the Great Basin for Mormons alone.

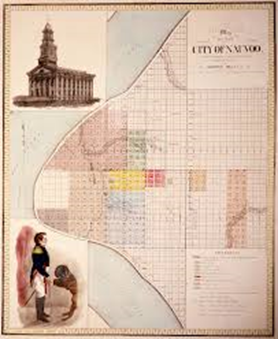

What preparation had the Mormons for that inevitable fact of western life? Mormons themselves may have been exclusionary at the beginning of their great social experiment. In Jackson County, they apparently informed their neighbors of their eventual doom as the Lord’s people took over — not the best way to make friends. But as Joseph Smith’s thought matured, he began to see his cities of Zion differently. His thinking reached its peak in Nauvoo, the city he erected on fetid swamp land on the banks of the Mississippi, and the one city over which he exercised control and brought to fruition.

Joseph thought of Nauvoo as an open city. One of the first acts after the city charter was obtained was to pass a religious tolerance ordinance.

“Be it ordained by the City Council of the City of Nauvoo, That the Catholics, Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, Latter-Day Saints, Quakers, Episcopalians, Universalists, Unitarians, Mohammedans, and all other religious sects, and denominations, whatever, shall have free toleration, and equal privileges, in this city.”

Early Nauvoo

Early Nauvoo

The act was remarkable for its time and place in welcoming Catholics and Muslims, religious groups widely disliked in Protestant America. But despite the prevailing prejudices, Joseph opened the city to all. He was an expansive person. He had immense confidence in the capacity of all people to work together. Running for president in 1844, he spoke out on the contested issues of relations with Canada and Mexico. There were tensions along both borders. Passing over the tangled details of the negotiations, Joseph rose to the level of high principle to declare: “Come Texas, come Mexico; come Canada; and come all the world — let us be brethren; let us be one great family; and let there be universal peace.” He thought all the outcasts of society could be incorporated into a happy society. By guaranteeing rights to all and welcoming them as brothers and sisters, all could be part of Zion. “I would as the universal friend of man, open the prisons, open the eyes; open the ears and open the hearts of all people, to behold and enjoy freedom, unadulterated freedom.”

Mormons are sometimes accused of being a parochial and clannish people, concerned only after themselves and interested only in making all the world Mormon. That was certainly not the view of their founding prophet. As he told the Twelve Apostles, “a man filled with the love of God, is not content with blessing his family alone, but ranges through the whole world anxious to bless the whole human family.” Joseph wanted Nauvoo to be a model city for all the world to look to, a city that would bless everyone, not just the Latter-day Saints.

That is the pioneer heritage, modern Mormons inherit from their founding prophet: to build model cities that will bless the whole world, cities in which people of all religions and backgrounds have a part. Do we really comprehend, do we understand the tremendous significance of that which we have? This is the summation of the generations of man, the concluding chapter in the entire panorama of the human experience. And how is this work to be prosecuted in a multicultural society? President Hinckley underscored the Joseph Smith ideal. The cities of Zion are not for Mormons only

Their goal was to make this society a Zion — a place of unity, justice, and freedom, not just for the Mormons, but for all people who dwell here. The work of modern pioneers is to make the cities of our region models of justice and peace, models for the world to look upon, models that would make Joseph Smith proud. When we do, a brighter day will surely dawn.

Sources:

- Times & Seasons, March 1, 1841, 336-37.

- Joseph Smith, Jr., General Smith’s Views of the Power and Policy of the Government of the United States (Nauvoo, Ill.: John Taylor, 1844). 7.8.

- Joseph Smith to the Twelve, October 1840, in Joseph Smith Jr., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2d ed. rev.,, 7 vols., ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1971), 4:227.

- Ensign (May 2004), 81.2.